The

Highland Township Historical Society |

|---|

Highland Trivia

Interesting Or Curious Facts Relating To Our Community And Its History

How Many "Highlands" Are There?

Highland's First And Last Government Land Patents

When Highland "Included" Its Neighboring Townships

When Highland Station Had A Weather Station

The Ill-Fated Clinton-Kalamazoo Canal: Highland's Waterway That Wasn't

![]()

How Many "Highlands" Are There?

According to the U.S. Board on Geographic Names (USBGN) there are at least 53 "minor civil divisions" in the United States known as the "Township of Highland." Of these, 25 are deemed "inactive;" meaning they no longer exercise independent authority, either because they have been subsumed by an incorporated city or merged with some other unit of government. Curiously, 10 of these 53 Highland townships (all "inactive") are located in Iowa - a state not known for hilly or elevated terrain! Perhaps more surprising, our Oakland County community is not among this list of 53! Rather, since September 1, 1995, the USBGN deems our "official" name to be "Charter Township of Highland," reflecting our adoption of a charter form of government in 1982, although "Township of Highland" is recognized as a "Variant name."

It is also interesting that at least one of these "other" Highland's, i.e., in Brown County, South Dakota, is named after our Michigan community. As noted in Doane Robinson, History of South Dakota, B.F. Bowen & Co (1904), Vol. II, pp. 1232, one of the first settlers in Brown County was Henry Clay Andrus. A native of Highland, Oakland County, Michigan, he settled in that part of Brown county "... which was afterward segregated and named Highland township, this title having been suggested by him, in honor of the township in which he was born, in the old Wolverine state." Whether any of the other Highland's were also so named is presently unknown.

In terms of post offices and other "populated places" with the name "Highland," USBGN puts the total at 70, including five deemed "historical," e.g. the name has since been changed or the town abandoned. Of these 70, the greatest number, i.e., 7, are located in Tennessee. This time our Oakland County community is on the list, since "Highland, Michigan" is our official postal designation. Of course, if one includes variant spellings like "Hiland" or "Hyland," plus compound names such as "Highland Park," then the list of such places numbers in the hundreds.

For more information, visit the U.S. Geological Survey's Geographic Names Information Service site at http://geonames.usgs.gov/pls/gnispublic/

![]()

Highland's First And Last Government Land Patents

The "first" patent issued by the U.S. Government evidencing the purchase of land in Highland Township turns out to have been a mistake, although it took over 100 years to correct! On April 16, 1823, a patent was issued for 80 acres of land described as the "West half of the North West quarter of section Ten in Township Three North of Range Seven East in the District of Detroit and Territory of Michigan..." As discussed in Understanding The Michigan Baseline And Meridian Survey System, Township "three north of range seven east" is the "official" description of Highland Township in the original government surveys. The person to whom such patent was issued was none other than Augustus B. Woodward, Chief Justice of the Michigan Territory, for whom Detroit's Woodward Avenue is named. As it turns out, however, the scrivener who filled in the description on the patent form made a crucial mistake - rather than Township three north, range seven east, Woodward had actually purchased 80 acres in Township three south, range seven east, i.e., modern day Ypsilanti township! The error apparently went unnoticed for more than a century, however, before the U. S. Government issued a new and "corrected" patent on February 21, 1927; canceling the 1823 grant since "the land was erroneously described as in Township three north."

Following the erroneous patent issued to Woodward, no patents were issued for land in Highland for another eleven years, Then, on September 10, 1834, a series of patents were given to Rufus Tenny, Alvah Tenny, Naham Curtis, Luther Parshall, Saviel Aldrich, Richard Willets and Samuel P. Noyes, Jr. Note that this does not mean these gentlemen all made their purchase at the same time. The physical act of picking out the land and tendering the purchase price took place at the U.S. Land Office in Detroit. Records of such purchases were then periodically sent to Washington, D.C., where the patents were prepared, signed and sent to the purchaser; often weeks or months after the actual sale. In the case of Woodward's purchase in Ypsilanti, for example, the official date for his patent (the correct one) is February 21, 1927.

The last patent for land in Highland Township was issued on January 22, 1926, to Harry S. Beaumont for 40 acres described as the southeast quarter of the northeast quarter of Section 12. Why did it take so long for someone to purchase this particular parcel? As a quick look at a Highland map will disclose, the entire 40 acres lies under the surface of White Lake! Since Beaumont owned other adjoining land, however, he presumably felt it in his interest to own this parcel under the lake as well. As noted elsewhere on this site, attempts had been made in the past to drain White Lake. Were this to occur, this submerged parcel might suddenly become a valuable piece of rich "bottom land." Alternatively, ownership of the parcel may have avoided problems when the Beaumont property was developed as the Seven Harbors subdivision, including dredging canals, erecting docks, etc.

As for the property that 1820 patent mistakenly granted to Augustus B. Woodward, it was patented "again" on August 18, 1837. Andrew Sorley was granted the northwest quarter of the northwest quarter of Section 10, while Garret J. Simonson was granted the southwest quarter of the northwest quarter. One would think the issuance of these patents covering the same property previously conveyed to Woodward would have brought the error to someone's attention much sooner than it did. Such was not the case, however, and both men were given patents to lands that another earlier patent declared, albeit erroneously, someone else already owned!

![]()

When Highland "Included" Neighboring Townships

Just as the Michigan Territory once included lands which are now other states (i.e., Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, and the eastern parts of North and South Dakota), so too did Highland Township once - albeit briefly - exercise authority over adjoining townships in both Oakland and Livingston Counties. As noted elsewhere on this site, Highland was organized as a separate and distinct township by an act of the Territorial legislature approved March 17, 1835. Just nine days later, on March 26, 1835, another act was passed by which:

... all that part of the county of Oakland comprised in surveyed township three north, range eight east, and township four north, range seven east, and all that part of the county of Livingston attached to the county of Oakland for judicial purposes, shall be attached to and comprise a part of the township of Highland, for the purposes of township government.

Laws of the Territory of Michigan, W.S. George & Co., Lansing (1874), Vol. III, p. 1404

The Oakland County townships described

by such language are what would become White Lake (Township 3 North, Range 8 East) and

Rose (Township 4 North, Range 7 East), while the Livingston County communities included

all eight townships in the northern half of that county [Ftnte 1]. As a

result of this legislation, the handful of settlers living in these as-yet unorganized

townships were provided a place to vote and collect their mail, as well as the right to

call upon the services of Highland's constable, justice of the peace and other township

officers.

Of course, as each of these outlying areas grew in population, they were quickly

organized as independent townships over which Highland no longer exercised

jurisdiction. White Lake, for example, became a separate township in 1836, followed

by Rose in 1837. The Livingston county townships were likewise separated from

Highland in 1836. Most were "attached" to Howell Township, although Tyrone

was initially included in Deerfield Township before being organized as an independent

township in its own right in 1838.

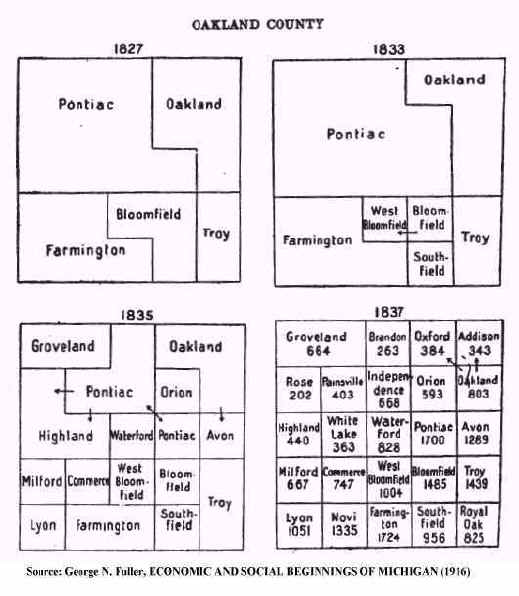

The maps at right illustrates this process. Thus, from 1827 to 1833 all of northwest Oakland County - including future Highland Township - was "attached to" and part of Pontiac Township. By 1835, however, the area overseen by Pontiac had diminished after the organization of Groveland (including Holly), Highland (including Rose and White Lake), Waterford and Orion Townships. By the time the 1837 Michigan State Census was taken 24 of the 25 townships in Oakland County had been officially organized (Holly being the exception) and reported the respective populations shown.

But while Highland's authority over its neighboring future townships was brief, it is nonetheless important to recognize and recall. Consider, for example, the case of Henry Phelps; an early settler in what would become Rose Township, who testified years later he had lived "in Highland." Given that Rose was "... attached to and comprise(d) a part of the township of Highland..." at the time Phelps lived there such testimony was, strictly speaking, true. At the same time it is easy to see how it might confuse anyone trying to research Phelp's history today. So too, several of the officers elected at Highland's first township meeting in 1835 were actually settlers in White Lake, Hartland and other townships then "attached" to Highland. For such reasons, claims that an individual "settled in Highland Township" during this early period should be considered carefully, as it is possible the actual place of physical settlement was elsewhere.

Ftnte 1 - The eight townships in the north half of Livingston County were previously part of Shiawasee County and, before that, Oakland County. Until the local county courts were established, however, they remained "attached" to Oakland County for judicial purposes.

![]()

As is well known, political boundaries do not always follow "natural" boundaries such as rivers and lakes. Situations can thus arise where it is impossible to travel by land from one part of a country, state or province without passing through another. Notable examples include Michigan's Lower and Upper Peninsulas; the part of Virginia located on the Delmarva Peninsula; and the Northwest Angle in Minnesota. If there is a technical, geographic term for these situations we would love to know it!

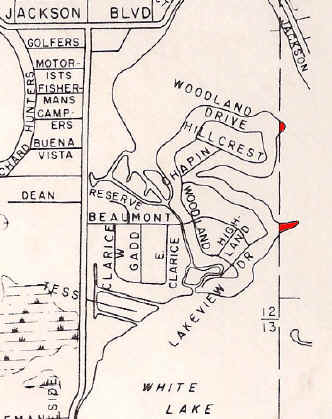

A similar situation exists - albeit on a much smaller scale - with respect to one [and perhaps two] tiny parcels of land which, while technically part of White Lake Township, can only be reached by land through Highland Township. These are shown here in red on this map of the Seven Harbors Subdivision in Section 12 of Highland Township.

The larger, southerly parcel lies just east of the point where Lakeview Drive makes a sharp jog and is improved with a single family home. In the days before White Lake's water level was artificially maintained, this parcel marked the start of a sandy isthmus which, if the water level was especially low, stretched east to Dawson's Island. Some USGS topographic maps still show such an isthmus, even though it is now submerged. The shallowness of the water in this area can be plainly seen, however, on aerial photographs such as those found on Google Maps.

The status of the second, smaller parcel to the north is less clear since its existence depends not only on the water level in White Lake, but on how accurately the boundary between the two townships is drawn at this point.

![]()

When Highland Station Had A Weather Station

By Eugene H. Beach, Jr.

NOTE: This item was originally published in Signpost - the newsletter of the Highland Township Historical Society. It is presented here both for its inherent interest as well as to illustrate the kinds of articles and notes our newsletter regularly contains.

Most current residents of Highland have probably heard of the Detroit/Pontiac (DTX) Weather Forecast Office in adjoining White Lake Township, Michigan. Operated by the National Weather Service, DTX is often mentioned in local media weather reports and its facilities are frequently toured by children on school field trips or scout troop outings. There was a time, however, when the task of observing and recording the weather was carried on within Highland itself, on a farm just a short distance north of Highland Station! To understand why and how this came to be, however, requires some historical background.

The National Weather Service owes

its existence to the weather of Michigan and other Great Lakes states. As commercial shipping increased, so too did the

damage caused by violent weather. In 1868 and

1869 over 3,000 ships were damaged or sunk and 530 lives lost due to Great Lakes storms. Professor Increase Lapham of Milwaukee sent news

accounts of these tragedies to Congress, which responded in early 1870 by requiring the

War Department to begin making weather observations at military posts and “…

giving notice on the northern (i.e. Great) Lakes and on the seacoast by magnetic telegraph

and marine signals, of the approach and force of storms.” The work was assigned to the Army Signal Corp,

which quickly established some two-dozen reporting stations that wired their observations

to Washington, D.C. three times each day. [Note 1]

Since the initial focus was

protecting maritime commerce, most of these early reporting stations were on the

lakeshores and seacoasts. As a result,

weather conditions in much of the country’s interior remained unknown. To remedy this situation, Gen. William B. Hazen,

US Army Signal Corps, sent letters to all state governors in 1881 encouraging the creation

and development of state weather services that could work cooperatively with the national

bureau. Michigan was among the states that

responded positively, establishing the Michigan State Weather Service (MSWS) in 1887. [Note

2]

The workings of the MSWS are well-described in its 1896 Annual Report. In his introductory letter to Governor Hazen S. Pingree, MSWS Director C. F. Schneider noted that:

The observation work is performed by a corps of voluntary observers

who do their work without remuneration of any kind except the receipt of the publications

of this office and the department at Washington. In

the location of stations the aim has been to give them to the principal cities and towns

of the various counties as well as to observe an even distribution. The usual equipment of

a station consists of an instrument shelter, a standard thermometer, a self registering

maximum thermometer, a self registering minimum thermometer and a rain and snow

gage…"

An accompanying engraving,

reproduced here, depicts the typical “instrument shelter” mentioned above; the

design of which has changed little to this day.

Given this description, it seems clear the MSWS was not in the business of making short-range weather forecasts. Rather, its focus was the systematic collection of data that would provide a better, over-all picture of Michigan’s climate. As Director Schneider wrote:

"This service has now in operation a station in nearly every county of the State where a continuous record is being made from day to day, of temperature, precipitation, wind, cloudiness and kindred phenomena. These records are being constantly referred to by many interests and classes of people… Cities and towns contemplating the laying out of new sewer systems have constant recourse to our rainfall data; it enables the engineer to carefully estimate the size of the sewer so that it will be large enough to carry off the heaviest downpour of rain and on the other hand it limits their size and thus regulates the expense... The various meteorological data is exceedingly valuable to physicians throughout the State who can study diseases with accurate and reliable meteorological facts by their side; for sanitary purposes correct meteorological statistics are invaluable to the practitioner in applying preventative remedies for the public good…

The data in the course of time will establish a climatology that must be valuable to any locality in the study and adaptation of its agricultural resources and it gives to nearly every county in the State the government standards for temperature and rainfall which are sources of useful public information."

Having thus reviewed the nature and purpose of the MSWS’ activities, Director Schneider concluded his introductory letter by acknowledging its “corps of voluntary observers,” noting that:

"Without considerable active and loyal cooperation much of the work of this service would be impossible. Interest and pleasure in the observation work has partly been the motive of much of this cooperation but beyond all this there is a public spiritedness that should be highly commended."

Among such “public spirited” volunteers was Highland Township’s own Archibald D. DeGarmo. Born July 12, 1845, at Ypsilanti, Michigan, “A. D.” (as he was more commonly known) DeGarmo came to Highland township with his parents in 1861, taking up residence on Milford Road, just north of Highland Cemetery. Here he soon became the very model of a “progressive” or “scientific” farmer. With his father he pioneered the introduction of shorthorn cattle into Michigan, winning numerous prizes at various fairs and exhibitions. He was likewise among the first to experiment with growing alfalfa, owned the first grain binder brought into the community, and employed a windmill and pipe system to irrigate his fields.[Note 3] It was thus wholly in character that A. D. DeGarmo should volunteer to be one of the “climate and crop correspondents” on whom the Michigan State Weather Service so heavily relied.

DeGarmo’s weather observations find frequent mention in MSWS’ annual reports and other publications. For example, the Monthly Weather Bulletin for April, 1896, shows that the average temperature at “Highland Station” for that month was 53.4 degrees; 8 degrees above the normal monthly average of 45.3 degrees. The highest reading for the month was a balmy 85 degrees on April 16th, while the coldest reading was a chilly 16 degrees on April 2nd, just two weeks before. Similar charts and tables give the dates and amounts of rain and snowfall during the year.

Since the Michigan State Weather Service data was shared with the National Weather Service, DeGarmo’s observations likewise found their way into reports and publications of the federal agency. For example, the Monthly Weather Review for February, 1889, shows that Highland Station experienced 13.5 inches of snow during that month. Likewise, the Monthly Weather Review for September, 1889, in a summary of Michigan weather, notes that “The maximum temperature for the month, 95, occurred on the 9th, at Highland station…” The following year the Monthly Weather Review for November, 1890, records that:

Michigan

Temperature – The mean was 1.8 above the normal of 15 years; maximum, 70, at Highland Station, 9th; minimum, 11, at Highland Station, North Marshall, and Ypsilanti, 28th; greatest monthly range, 59, at Highland Station…

Precisely when DeGarmo first became a volunteer weather observer, and for how long he so served is unknown. The earliest reference thus far found to the observation station in Highland are in the 1889 issues of Monthly Weather Review quoted above. So too the last mention found appears in the Michigan Manuel for 1899. The search has thus far been limited, however, to volumes scanned by Google and a more extensive search of the physical books themselves might disclose earlier and/or later references.

At a minimum, however, it seems there is a decade or more of

observations made by A.D. DeGarmo of the weather at Highland Station. Were such data

located, abstracted, compiled and analyzed it should provide a good overall picture of the

township’s climate a century ago. This means – at least in theory –

one might at last prove or disprove the claims so often made by “old timers”

that their childhood winters were always colder, the snows always deeper and/or the

summers always hotter than those the “younger generation” now experiences.

That exercise, however, is left to another day.

NOTES:

[1] The Detroit/Pontiac Weather Forecast Office has a short “History of the NOAA National Weather Service In Southeast Michigan” on its web site at: http://www.crh.noaa.gov/dtx/history.php The National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) also has a short history of the National Weather Service on its site at http://www.history.noaa.gov/stories_tales/bur1.html

[2] See “United States Climatological Chronology” by Paul Waite, Former State Climatologist of Iowa, at http://weather.nmsu.edu/USClimat.htm For a history of the legislation creating the Michigan State Weather Service, See: Annual Report of the Attorney General of the State of Michigan for the Year Ending June 30, 1898, pp. 63-66. Note that the Michigan State Weather Service survived until 1980, when it was abolished by the Legislature as a cost-cutting move.

[3]

Clara Mae Beach, Our Highland Heritage, p. 110, contains a good summary of A.D. DeGarmo’s “progressive” approach toward farming. Something of the man’s character can also be gleaned from an amusing anecdote found in Elam E. Branch, History of Ionia County, Michigan, B. F. Bowen & Co. (1916), pp. 150-151. Describing DeGarmo as “a Republican, with inclinations toward Socialism,” this source claims “The only public office to which he ever was elected was that of township clerk, on the Republican ticket, in 1872. Tiring of the office, he turned the same over to a Democratic neighbor, which act served effectually to ‘cut off his political head.’”![]()

The

Ill-Fated Clinton-Kalamazoo Canal:

Highland's Waterway That Wasn't

Highland Township's numerous lakes make it a boater's paradise for residents and visitors alike. Unfortunately, all such lakes are either "landlocked" or the creeks and streams which flow from them are unsuited to navigation. As a result, those wishing to cruise more open waters must either haul or dock their boats elsewhere. But suppose it were possible to travel by water all the way from Highland to either Lake Michigan or Lake St. Clair? For a few brief years following the township's establishment that "dream" seemed close to becoming reality.

The success of New York's Erie Canal (completed in 1825) stimulated a brief but intense interest in canal building throughout the country. Michigan was no exception to this frenzy, especially since so many of its early settlers had themselves used the Erie Canal on their journey west. The state's geography also made construction of a canal seem both necessary and feasible. Although the Lower Peninsula is surrounded on three sides by water, sailing from Detroit to Benton Harbor requires a long (roughly 750 miles), time-consuming and often hazardous voyage up Lakes St. Clair and Huron, through the Straits of Mackinac, then down the east coast of Lake Michigan. In contrast, a canal across the base of the Lower Peninsula could cut the distance by two-thirds, reduce the risks of travel and open the state's interior to both settlement and commerce. So too, the relatively flat terrain would reduce the need for expensive locks, while an abundance of inland rivers, streams and lakes could readily supply such a canal with water.

Flush with excitement following its admission to the union in 1837, Michigan embarked on an ambitious program of "internal improvements." Among these was the Clinton-Kalamazoo Canal, a 216 mile waterway across the state. Beginning at Lake St. Clair near Mt. Clemens, it would proceed up the Clinton River to Pontiac, then head west through Howell, Mason, Vermontville and Hastings until it reached the mouth of the Kalamazoo River on Lake Michigan. Actual construction began on July 20, 1838, when:

"... with blare of trumpets, and salute of guns, ground was broken by the governor in the presence of a vast concourse of citizens for the work at Mt. Clemens. Detroit was there en-masse. At daybreak the firing of a gun announced the dawn of a day those who then lived would mark a great era in the life of the commonwealth.

Pointing out the great results which must follow the completion of the canal, Governor Mason, the idol of the state, turned the first shovelful of earth."

Paul Leake, History of Detroit, Lewis Publishing Co., Chicago (1912), Vol. I, p. 137

The enthusiasm generated by this event is well-illustrated by John N. Ingersoll, a correspondent for the Detroit Journal and Courier, who described it as "... a day which will be recollected by the people of Michigan as the proudest that ever happened, or can again transpire while her soil remains a component part of terra firma."

Even before work began, however, circumstances conspired against the canal's completion. The so-called "Panic of 1837" prompted a prolonged depression, making it difficult for the state to sell the bonds necessary to finance the project. Thus, as early as April 1, 1839, a committee of the Michigan House of Representatives reported that "... such is the situation of the internal improvement fund, it was deemed prudent and advisable ... to instruct, by resolution, the board of Commissioners to suspend all operations west of Howell, in Livingston county,..." p. 397, Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Michigan - 1839, J. S. and S.A. Bagg, Detroit (1839). With money scarce contractors soon went bankrupt and unpaid workers quit. Moreover, the prospect of competition from the state's new railroads - which were both faster and cheaper to build - cast further doubt on the project's wisdom. Thus, by the time work finally ceased on the canal in 1843, it had progressed only as far as Rochester, a distance of approximately 12 miles. All but useless as a means of travel, portions of it were soon converted for use as a mill race.

The dream the Clinton-Kalamazoo Canal represented, however, took somewhat longer to fade. As noted in the History of Livingston County, Michigan, Everts & Abbott (1880), p. 54:

But, for a period of about ten years from the inception of these projects, strong hopes were entertained by many that they would ultimately be completed; and extravagant expectations were indulged in of great advantages to accrue in consequence, to the county, and particularly to certain localities along the projected line. As late as 1845 the matter was discussed in the public prints in a manner showing that there was still abundant confidence among the people in the accomplishment of the scheme and in the great and beneficial results sure to follow. An editorial article, which appeared in the Detroit Advertiser in February of that year, in speaking of the main canal, and of a change of route which seemed to the writer to be desirable, said that "the western route of the canal should be so modified that, after leaving the Clinton River and the small lakes of Oakland and Livingston Counties, it should pass down the valleys of the Red Cedar and Grand Rivers to Lyons, Ionia County, and to the head of navigation on Grand River," and added that the work appeared to be second in importance only to that of the Central Railroad."

The fact there is a "Canal Street" in Howell further

attests to the hopes such projects inspired.

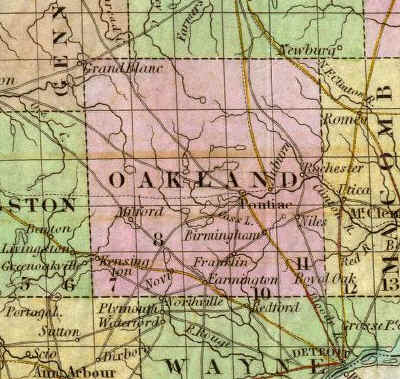

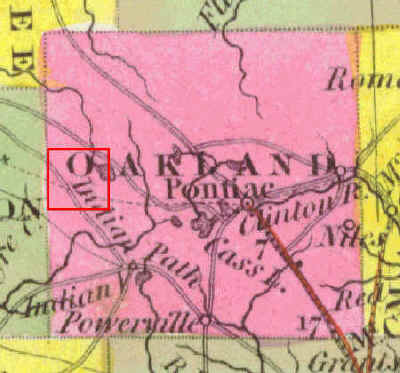

From a variety of evidence it seems certain that the Clinton-Kalamazoo Canal would have, if completed, passed through Highland. Part of the "small lakes" region of Oakland county, the township lies more or less midway on the most direct line between Pontiac and Howell. Indeed, such a proposed route is depicted in Thomas R. Tanner's New & Authentic Map of the State of Michigan and Territory of Wisconsin, published in 1839. The illustration at right is an enlargement of the Oakland County portion, with Highland being the township containing the letter "O." Notice White Lake in the northeast corner, as well as two of the old Indian trails that once crossed the township: the Shiawassee Trail in the southwest, and the White Lake Trail in the northeast (modern Rose Center Road). Of most interest for present purposes, however, is the dashed line representing the proposed route of the Clinton-Kalamazoo Canal. As can be seen, it appears to enter the township roughly between Sections 25 and 36, then head more or less due west before entering Hartland Township. Along the way it would intersect, and perhaps have been fed by, the waters of Pettibone Creek.

A slightly different route is

depicted in Samuel Augustus Mitchell, A New Map of Michigan With Its Canals, Roads

& Distances, published in 1847. The illustration at left is an enlargement

of the Oakland County portion. While individual townships are not drawn, the area

occupied by Highland is outlined in red. Notice White Lake, visible between the

"O" and "A" in "OAKLAND." Two "Indian

paths" are again shown, along with a dashed line representing the Clinton-Kalamazoo

Canal. Unlike Tanner's 1839 map, however, Mitchell suggests the route would have run

slightly west-northwest, skirting the south shore of Dunham Lake before entering Hartland

Township.

A slightly different route is

depicted in Samuel Augustus Mitchell, A New Map of Michigan With Its Canals, Roads

& Distances, published in 1847. The illustration at left is an enlargement

of the Oakland County portion. While individual townships are not drawn, the area

occupied by Highland is outlined in red. Notice White Lake, visible between the

"O" and "A" in "OAKLAND." Two "Indian

paths" are again shown, along with a dashed line representing the Clinton-Kalamazoo

Canal. Unlike Tanner's 1839 map, however, Mitchell suggests the route would have run

slightly west-northwest, skirting the south shore of Dunham Lake before entering Hartland

Township.

In the end, of course, the Clinton-Kalamazoo Canal amounted to little more than what is seen here - mere lines on a map. While remnants of the portion actually built can still be seen, and are the subject of both state and local historical markers, most today have never heard of the canal, much less know of its proposed route. As the references above suggest, however, such was not the case in the late 1830's/early 1840's. Given the public celebrations and frequent newspaper accounts, plans for the canal - including its proposed route - were undoubtedly "common knowledge" and a topic of discussion in taverns, stores, churches and homes. There is at least one first-hand account indicating that the canal's proposed route through Vermontville prompted a pioneer family to locate there, See: Edward W. Barber, "Recollections And Lessons of Pioneer Boyhood," Michigan Pioneer And Historical Collections (1902), Vol. XXXI, p. 183. One thus wonders if the same might have been true of one or more early Highland settlers.

![]()